Ushitsu Abare Festival

・・・・・・・・・・

Hello everyone, how are you all? This is Tanaka from GRIDFRAME.

On Friday, July 5th and Saturday, July 6th, the Abare Festival was held in Ushitsu, Oku-Noto.

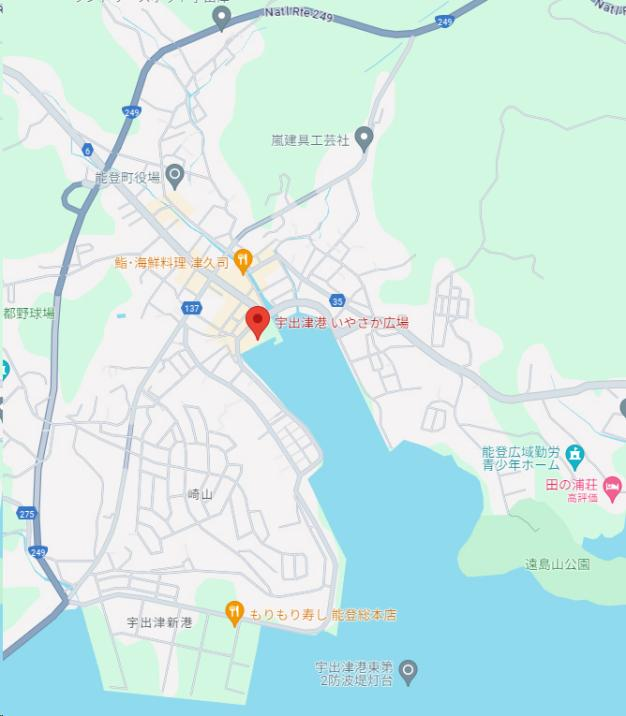

Ushitsu is located in a clearly enclosed, symmetrical area, with Ushitsu Port open to the south at its center, and Sakadaru Shrine to the west, Hakusan Shrine to the east, and Yasaka Shrine to the north, surrounded on three sides by hills.

The terrain makes you feel like you’re in Ushitsu no matter where you are. Perhaps it’s precisely because of this location that the festival has continued for over 350 years.

“As this season approaches, I get the smell of the forest and the sea and start to get excited, thinking, ‘Doesn’t this feel like a festival?'” (local woman in her 20s)

Festivals are integrated into the rhythms of the hearts and bodies of the local people. Young people who have left their hometowns may not return for Obon or New Year, but they always come back for the festivals. The festival day marks the end of one year and the beginning of a new one. For example, they will have their air conditioner repaired by the time of the festival day. They will also buy new clothes. …It would be unthinkable not to participate in the festival.

However, given the dire situation caused by the earthquake, many people were opposed to holding the festival, and the decision was made to go ahead amid much debate. I hear that the older generation, understanding that the young people’s desire to hold a festival would pave the way for the town’s future, accepted the responsibility.

This time, together with M, I participated in the “Abare Matsuri Project” run by Matsurism’s Ohara Manabu and Sukegawa Fumie, staying in the Ushitsu area from July 3rd (Wed) to 7th (Sun), and helped carry the kiriko. The earthquake hit an area that was already suffering from depopulation, and this has only made the situation worse. Carriers from outside are needed to move the kiriko, which weighs nearly two tonnes.

As I wrote in Vol. 5, my purpose in participating was to experience the festival, a chaotic space where people willingly gather, in order to explore the direction of “reshaping the chaotic state of the disaster-stricken areas while preserving as much chaos as possible.”

<Festival of Madness>

The Abare Festival begins with two portable shrines (mikoshi) setting off from Yasaka Shrine, heading for Sakadaru Shrine and Hakusan Shrine, respectively, and parading through town to instill positive energy into the local area, its people, and its objects, before returning to Yasaka Shrine. 40 kiriko (31 this year) from each region accompany the mikoshi as sacred lanterns. To worship Susanoo-no-Mikoto, who takes delight in wild behavior, the kiriko approach a blazing torch as if charging, showering all the carriers with sparks. The mikoshi is then thrown into the river, turned upside down, rolled, burned, and the participants boast about how badly they can destroy it – a pretty crazy festival. It can be described as “an extremely crude festival that is extremely complex and meticulously planned.”

Before we carried the kiriko and charged into the fire, a local person very quietly and politely explained to us, “It’s said to be uncool to brush off falling sparks,” and I, too, felt sparks sticking to my little finger, and cried out in my head, “My fingers!”, but I just continued to carry the kiriko quietly. Other participants also had holes in their clothes, parts of their hair burned, and multiple welts on their necks…but everyone was happy to show them off to others, making it a festival that turns normal people (?) into madmen lol.

I decided to carry the float after Ohara told me, “People who just watch won’t come back next year, but people who carry it will want to come back next year.” So I was curious to see what I would feel by participating.

Kiriko are said to weigh between 1 and 2 tons. Five or six children and women stand on top of them, beating drums and playing flutes, so I think it’s probably closer to 2 tons. They are carried by around 30 men and women. Each person has their own cushion, which they hang from the carrying pole and rest their shoulders on.

First of all, the height of the poles was not right for my shoulders, and I became anxious because I was not able to use any strength at all. When I told them that, they changed the position, and now the weight was weighing down on my shoulders, which I could not support. From then on, I had to carry the kiriko with almost all my strength, otherwise it would stop. I had to hold it in a position where I could not relax.

At that point, I entered a world of guts, and as I carried the team, following the calls of the young boss, Shouji-san, I nostalgically recalled the athletic atmosphere of my childhood when I practiced judo. I remembered how back then, whenever the team lost, I automatically thought it was my fault.

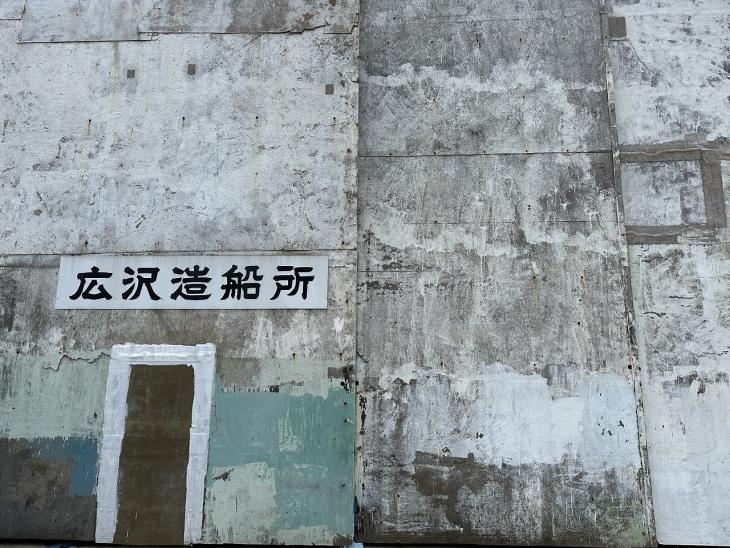

Even as I struggled to carry the simple act of carrying it, watching the scenery change from where I was sitting (broken buildings, shouts, lights in the windows, shutters that wouldn’t open, spectators, smiling faces, leaning houses, weathered walls, one-liter bottles of sake, stone bridges, rivers, subsidence, murmurings, torches, sparks, flutes, drums…), it felt like I was watching a long movie by myself.

Is Ushitsu happy? People with calm expressions. Dilapidated buildings with quiet smiles.

I hope you’re safe and happy festival!

(I remember reading in a book by Mori Atsushi that “the word ‘un’ is written as ‘carry’ but is read as ‘un’ (luck).” I sincerely pray for good fortune for everyone!)

<The souls that reside in things are in the ruined town>

As I walked slowly through the landscape around Ushitsu Port, where the festivals are held, I was greeted by a landscape filled with SOTOCHIKU elements that excited me. As soon as I reached the southwest end of the area and made a right-angle turn toward Ushitsu New Port, the landscape changed to a nondescript one you’d find anywhere. There were large supermarkets, chain restaurants, and other large stores.

At a glance, anyone can tell the difference between the two.

There is a soul (god) residing on the Ushitsu Port side, but no soul (god) can be felt on the Ushitsu New Port side.

So the former has festivals and the latter does not.

However, the former has a group of buildings with old, heavy tiled roofs, while the latter has a group of steel-framed buildings with lighter roofs.

The former is severely affected by the earthquake, while the latter does not feel any serious impact.

In other words, when we think about the future of Noto, if the challenge is simply to “build buildings that will not collapse even in an earthquake,” the answer is clearly that lightweight structures like prefabricated buildings will suffice.

But there is no soul in it, and that is the problem.

Aren’t we currently creating things all over Japan (and the world) that have no soul?

Wouldn’t that mean losing festivals, and in turn losing the culture that instills the right vibrations into communities, people, and things every year?

I think there are many people, both local and outside, who think that Noto would no longer be Noto without festivals.

So, while the remains of these broken objects that house souls remain, why not use them to create walls or gates? It might also be good to cover part of the exterior wall of a new building after it has been constructed.

How about using the things destroyed in the earthquake as precious materials that remember time, and reconstructing the landscape of Noto?

<Compared to life in Tokyo>

Also, having the opportunity to participate in Ushitsu’s Abare Festival, I strongly felt that thinking about the future of Ushitsu can only begin with feeling a sense of crisis about my life in Tokyo.

I heard that in Ushitsu, immediately after the New Year’s Day earthquake, young people went around to homes where elderly people lived and urged them to evacuate. It has been pointed out that the fact that human casualties seem to be less than material damage is largely due to the mutual aid system that has been built up within the festival.

Tokyo has many festivals, but the connection between them and my life has always been tenuous. In fact, you could say I’ve tried to stay away from them. Originally, Tokyo was a gathering place for people who came to the city hoping to break free from the communal constraints typically associated with rural areas. The majority of people there tend to be passive about communal activities. It’s now common for residents of the same apartment building to not even make eye contact when they bump into each other in the elevator, and there’s no system in place for mutual assistance in case something happens. I want to do something about the current situation where people have no choice but to protect themselves. I think this is one of the purposes of Tokyo’s many festivals.

So, can a festival that fosters a sense of mutual assistance be established in the area where I live? This experience made me realize that one of the most important prerequisites for this is the creation of a landscape surrounded by things that have a soul. I would like to take another look at the town where I live with this in mind.

<When you lose something important>

In vol. 5 I wrote:

“The goal of SOTOCHIKU materials is to preserve the narrative, while the goal of revitalizing the burnt-out areas of the area must be to transform that narrative, which is what we can see as opposing vectors.”

The damage caused by the Noto Peninsula earthquake varies from place to place, making it difficult to generalize. The above text was written with the scorched earth of Wajima Morning Market, which was completely untouched at the time, in mind.

However, as I continue to observe the situation in various disaster-stricken areas, I feel that unless we advocate a “narrative transformation,” it is inevitable that the destroyed objects will be swept away like garbage and replaced with buildings that lack a soul.

So, what does “narrative transformation” mean? I wrote a blog post about a “narrative transformation” that happened to me, and I’ll reprint it here.

・・・・・・・・・

What do people fear most when they lose something important?

And what would you want?

I often remember when I lost my father.

On December 1, 2010, my father died in a traffic accident in his hometown of Kumamoto. He was hit by a car going straight at night while crossing a street. He died instantly.

It was probably a little after 10 p.m. when my sister, who lives in Fukuoka, called me in Tokyo to tell me the news. I remember collapsing to the floor for a while.

The project proposal was due in the morning of the 2nd, so I got up and concentrated on preparing the proposal.

At that time, I think I was able to work calmly. The presentation was a success on the morning of the 2nd. After that, my family and I immediately headed to the airport.

On the way to Kumamoto, I remember beginning to fear one possibility.

I wonder if my father, who died in a traffic accident, is lying there in peace right now?

Occasionally, an image that is not true crosses my mind.

As we got closer to the funeral home, I was becoming more and more afraid of facing my father’s body.

If my father’s face wasn’t his usual calm face, I might not be able to stay calm.

“He must have passed away peacefully.”

I entered the venue with a prayerful feeling and immediately came face to face with my father.

“Thank goodness…” I couldn’t help but say. My father had died as if he was sleeping. His expression was the same as when he always dozed off while watching TV.

Now I’m thinking back to what I was afraid of back then.

Could it be that he was afraid that if the image of his father as a gentle man he had been when he was alive were shattered, something would crumble inside him?

Perhaps he wanted to forcefully imprint a story in his mind that “my father was a man who lived a happy life.”

I think that was necessary for me to live a bright future, and to continue protecting my family like my father did.

I believe that funerals are not just for the dead, but to create a foundation for those left behind to live in a world without them.

On the other hand, when each person left behind is able to weave their own story and build a foundation for the future, the funeral may become the first memorial for the deceased.

There are times when humans must stand up straight, even when they lose something important.

When my father passed away, what barely kept me going was the story that was brought to me by the calm expression on his face as he lay there.

I know how fragile I am, so whenever I face difficulties, I write stories and continue to search for light within them.

・・・・・・・・・

“Narrative transformation” here means that each person facing difficulties weaves their own story by confronting the situation one-on-one, thereby gaining the strength to support themselves and move forward into the future.

If there is anything we who create spaces can do, it is to create a space where each individual can face events one-on-one.

In the next issue, we will be sharing information about the SOTOCHIKU materials that will be donated in Noto.

July 31, 2024 GRIDFRAME Toshiro Tanaka

Comments are closed